UVA’s Public-Ivy Business Model

The University of Virginia (UVA) has adopted a high-tuition, high-aid business model, similar to that of Ivy League schools, which has engendered a vicious cycle of higher tuition, increased financial aid for lower-income students, and higher tuition to pay for the financial aid. The model may be unsustainable.

The average cost of attendance for in-state students is around $34,000, while out-of-state students face costs of $72,600, comparable to Ivy League tuition. Under some circumstances, UVA charges as much as Harvard. The cost of attendance for out-of-state students is prohibitive for middle-class families and puts UVA at a severe disadvantage in competing for the best and brightest students.

UVA endeavors to compensate for high tuition with an extensive financial aid program which offers full tuition, fees, room, and board for students from families earning less than $50,000; less generous packages for those earning up to $100,000; and a pittance for middle-class families earning up to $150,000.

To pay for that assistance, UVA redirects a significant portion (twenty-two percent) of undergraduate tuition revenue toward financial aid. Students from better-off families — out-of-state students most of all — effectively subsidize lower-income students by thousands of dollars each.

Recent trends raise questions about the long-term sustainability of the business model. As tuition climbs ever higher, out-of-state students are showing more price resistance; the percentage accepting UVA offers of admission has been declining for twenty years or more. Only one-in-six out-of-state student applicants accept.

But a clear understanding of how all the pieces work creates an opportunity. Reducing administrative overhead could allow for tuition cuts, which would in turn reduce the need for financial aid, providing a double round of relief for all students.

The High-Tuition, High-Aid Business Model

The University of Virginia has adopted a high-tuition, high-aid financial model similar to that of Ivy League and other elite private universities. The University is enmeshed in a vicious cycle in which every boost in tuition and fees requires more financial aid — which requires more resources, which requires more tuition revenue.

In the 2024-25 academic year, the weighted average cost of attendance for in-state undergraduate students is almost $34,000, according to the State Council of Higher Education for Virginia (SCHEV). But for an out-of-state undergrad, it hits at $72,600. Depending upon year and major, the cost could be comparable to that of going to Harvard.

“The University is enmeshed in a vicious cycle in which every boost in tuition and fees requires more financial aid — which requires more resources, which requires more tuition revenue.”

But just like car buyers, not everyone pays the sticker price. UVA offers generous financial aid for lower-income students. According to data published in SCHEV's most recent Tuition and Fees report, the net cost varies widely by income. For UVA students whose family incomes were $30,000 or less in the 2022-23 academic year, the average annual cost of attendance after grants and scholarships was $10,100. For students from families earning more than $110,000, the average cost was $34,800 — three times as much.

Like the Ivies, UVA uses its high-tuition, high-aid business model not just to make college more affordable for lower-income students but to make students from more affluent families help pay for them.

It's one thing for private universities to adopt income-redistribution policies aligned with the progressive ideological proclivities of their governing boards, It's a very different matter for a public university like UVA, which plays a critical role as the flagship institution for Virginia's public university system, to do so.

Like its predecessors, the Ryan administration showers the Board of Visitors with data, but it does not explain the fundamentals of its business model. Presentations to the Board treat tuition and financial aid as if they were separate and unrelated. The administration does not reveal how much tuition revenue is siphoned off to pay for financial aid.

With this report, The Jefferson Council endeavors to fill gaps in the public's understanding. Our investigation has concluded the following:

Tuition and fees for both in-state and out-of-state undergraduates are among the highest charged by any public university in the country. This is not a controversial conclusion; it is well documented by SCHEV.

UVA gives paltry relief to middle-class students. The high cost of attendance punishes all paying students. Affluent families may tolerate the high prices, but the elevated cost poses a much greater burden to middle-income families. Although the UVA Promise financial aid program provides $2,000 in relief to households earning as much as $150,000, the award covers a minuscule fraction of the cost.

The burden of the high-tuition, high-aid model falls hardest on out-of-state students. The sticker price for tuition and fees for full-time, out-of-state undergraduate students varies by college and year but typically exceeds $58,000 annually in 2024-25. Add the cost of room, board, and miscellaneous charges, and the total cost of attendance can approach $80,000 a year for some fields of study. The percentage of both in-state and out-of-state students accepting UVA offers of admission is plummeting.

High financial aid creates a financial treadmill. More than one-in-five dollars (twenty-two percent) paid in undergraduate tuition goes to financial aid. Each tuition hike creates a feedback loop: higher tuition ratchets up the University's financial aid obligations, which it in turn recoups through higher tuition.

The reverse multiplier effect. Every dollar in spending cuts translates into a dollar less in tuition. The resulting reduction generates another $0.22 in savings through diminished need for financial aid. Thus, slashing $100 million from academic division spending can save students $122 million in tuition payments.

“The high cost of attendance punishes all paying students.”

It is high time for the Board of Visitors to explore the relationship between tuition and financial aid and understand the implications for middle-class affordability and long-term financial sustainability.

The UVA Promise

The University of Virginia is not the only public university to adopt a high-tuition, high-aid financial model. Virginia’s public universities generally tend to charge higher undergraduate tuition and fees than their counterparts in other states.

Like other state legislatures, the Virginia General Assembly subsidizes in-state tuition through allocations from its general fund. The high tuition reflects lawmakers’ inability or unwillingness to meet the official goal of covering two-thirds of the cost of undergraduate tuition.

Meanwhile, successive UVA administrations have allowed costs to rise through mission creep, administrative bloat, and a commitment to boost the enrollment of minority, first-generation, and other “marginalized” populations. As tuition ratcheted upward, demand for financial aid has soared over the past thirty years.

In 2004, the University established its “AccessUVA” financial aid program, the centerpiece of which was its “UVA Promise”: UVA would cover every student’s demonstrated financial need. Here is what the UVA Promise looks like today:

Up to $50,000. The University will cover full tuition, fees, and on-Grounds housing and food for up to eight semesters for in-state undergraduate students in households earning less than $50,000 a year and reporting less than $100,000 in assets.

$50,000 to $100,000. The University will cover full tuition and fees for students in households earning less than $100,000 a year and reporting less than $100,000 in assets. Room and board are not included.

$100,000 to $150,000. The University will grant $2,000 to students in households earning less than $150,000 and reporting less than $150,000 in assets.

UVA adds up federal Pell grants, state Guaranteed Assistance grants, and other grants and scholarships that an undergraduate student might be awarded, and then covers the balance through the AccessUVA program. This umbrella entity draws upon university-funded AccessUVA Scholarships as well as nearly two hundred privately endowed scholarships.

The grants and scholarships are not designed to cover a student's full costs. Students are expected to borrow money, too. However, UVA says it caps need-based loans over four years at $4,000 for low-income Virginians, and at $18,000 for other Virginians with need. Loans for needy non-Virginians are capped at $28,000 over four years. Thus, middle-class students pay more in tuition than peers from lower-income families, and they graduate with the same earning potential conferred by a UVA degree — along with owing more debt.

Where Does The Money Come From?

Broadly speaking, there are two types of financial aid: grants (which don’t have to be repaid) and loans (which do). Financial-aid funds come from a variety of sources: federal grants and loans, state grants and loans, private scholarships, and, most importantly, two sources of UVA funds classified as “institutional” and “endowment.”

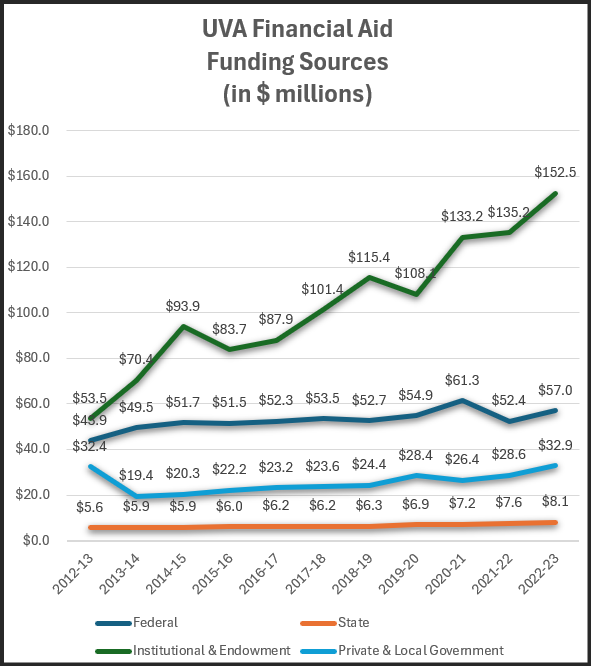

In the 2022-23 academic year, the most recent for which data is available, SCHEV reported $250 million in financial aid for UVA students from all sources. These included federal aid ($57 million), state aid ($8 million), and private and local government aid ($32.9 million). By far the largest source of financial aid was the University of Virginia itself — $152 million in institutional and endowment aid.

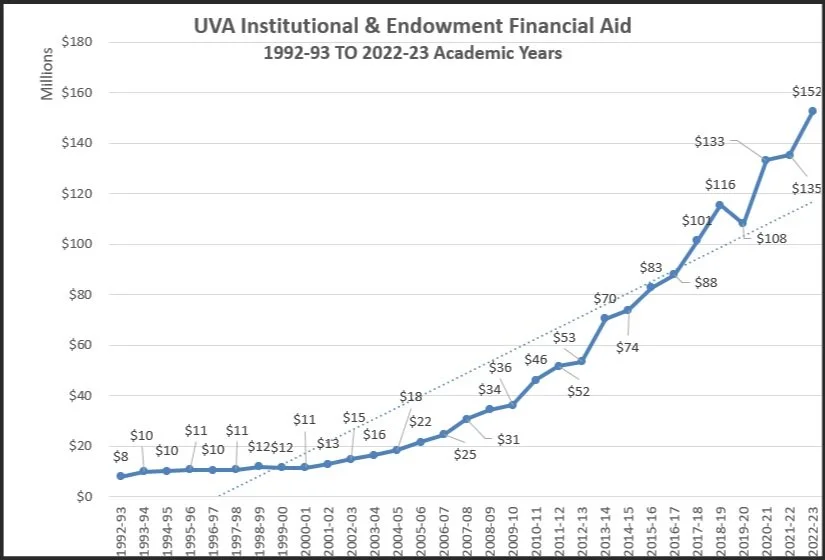

While the Consumer Price Index slightly more than doubled between 1992-93 and 2022-23, and the dollar value of federal loans soared by seven times, UVA financial aid for undergraduates shot up more than nineteen times, making it one of the fastest-growing components of spending.

FA17: Financial Aid Awards by Source (SOURCE: schev.edu)

Institutional aid comprised the biggest portion: $102 million in 2022-23, compared to $11.4 million, mostly scholarships, from UVA’s endowment.

The surge in financial aid was driven by three factors: (1) an increase in the number of students receiving the aid, (2) the amount of aid per student, and (3) the feedback loop of increasing aid to offset higher tuition.

According to SCHEV data, the number of UVA undergraduate students receiving institutional or endowment assistance leaped from 1,795 to 6,637 over the thirty year period. Although undergraduate enrollment increased by roughly thirty percent over that time, the percentage of students receiving student aid tripled from 8.3 percent to 25.5 percent.

Over the same period, the amount of UVA aid per student soared from $4,400 to $23,000, also far surpassing the inflation rate.

As seen in the graph above, the increase in financial aid proceeded slowly through the 1990s, accelerated modestly around 2000, then hit a new inflection point and accelerated yet again around the time of the Great Recession of 2007-08.

The Ryan administration has made an effort, with considerable success, to boost endowments for scholarships through its fundraising efforts. The University has seen several major gifts in recent years, including a $50 million gift from David Walentas toward the Walentas Scholars Program for first-generation students. In the June 2024 board meeting alone, the administration announced eleven gifts totaling $16.4 million for scholarships and graduate student fellowships.

On average, UVA spends 4.7 percent of its endowment each year, implying an ongoing annual income for scholarships and fellowships of $770,000 from the June gifts alone.

“To meet its UVA Promise obligations, UVA relies increasingly upon ‘institutional’ sources of funds, which consists primarily of tuition revenue.”

The generosity of such benefactions, along with supplemental dollars from the University’s Strategic Investment Fund, explains how UVA has been able to boost its scholarship aid substantially over the years.

Nevertheless, to meet its UVA Promise obligations, UVA relies increasingly upon "institutional" sources of funds, which consists primarily of tuition revenue.

With a few blips up and down, according to SCHEV data, institution-sourced financial aid has risen consistently as a percentage of tuition and fees since the 2010 academic year, the earliest year for which tuition and fees revenue is published.

Three decades ago, UVA did not use tuition revenue to fund financial aid. According to SCHEV data, grants from institutional funds leaped from zero dollars in 1992-93 to almost $102 million in 2022-23. The practice got off to a slow start but took off in 2001-02 with only an occasional interruption to its upward climb. By 2022-23, institutional aid was equivalent to almost fifteen percent of the University’s $691 million in tuition and fee revenue — one-in-seven dollars.

The trend from 2009-10 to 2022-23 looks like the chart below, and the percentage has climbed even higher since then.

FA17: Financial Aid Awards by Source (SOURCE: schev.edu and UVA annual financial reports)

According to a highly credible source, twenty-two percent of tuition revenue is now applied to financial aid. The mechanics work like this: The central UVA administration collects tuition revenue from students and funnels funds back to the College of Arts and Sciences and the various schools (engineering, commerce, nursing, etc.) in proportion to the share they are responsible for generating — with a twenty-two percent cut for financial aid. It is not clear if the twenty-two percent figure is directly comparable to the SCHEV numbers, but whatever discrepancies might exist, the upward trend is irrefutable. The Jefferson Council asked the UVA communications office to confirm the twenty-two percent number but received no response.

As spending on institutional and endowment funds has increased, these internal sources have become the largest contributor to financial aid at UVA, as seen in this graph based on SCHEV data — far surpassing the contributions of private, federal, state, and local government sources.

FA17: Financial Aid Awards by Source (SOURCE: schev.edu)

It is a legitimate question to ask how long the high-tuition, high-aid model can be sustained. The Ryan administration shows no sign of backing off its commitment to recruit more lower-income and first-generation students who need high levels of assistance. Although applications to UVA remain strong, there is arguably a limit to how long UVA can continue charging out-of-state students Ivy League tuition and fees for a degree that, though eminently respectable, confers less prestige.

The Out-Of-State Squeeze

Out-of-state students are UVA’s fiscal milch cows. The administration charges them as much as the market will bear so it can subsidize tuition for in-state and lower-income students.

In-state students comprise around two-thirds of the student body, and out-of-state students comprise about one-third, including international students. The Commonwealth of Virginia is contributing $239 million in aid to UVA this year with the expectation that the subsidy will be used to reduce in-state undergraduate tuition. That subsidy amounts to about $13,600 per student. Add the subsidy to in-state tuition and fees, and the weighted-average undergraduate tuition (not including room and board) comes out to $33,000 per head. Add another $20,000 for room, board, books, and personal expenses to get the total cost of attendance.

A UVA diploma has been in such high demand, however, that the University can charge out-of-state students far more — about $58,000 a year in tuition and fees. Charging out-of-state students what the market will bear is widely accepted among Virginia legislators as a useful tool for keeping in-state tuition lower. But in practice, more than one-fifth of tuition paid by all students goes toward subsidizing lower-income students — in particular, lower-income out-of-state students for whom the full cost of attendance is the most unaffordable of all.

According to SCHEV, UVA dispensed more financial aid to out-of-state students than to in-state students, and the gap gets wider with each passing year.

FA22: Financial Aid by Program (SOURCE: schev.edu)

Without aid, lower-income out-of-state students could never afford to attend UVA. The big losers from UVA’s business model are middle-class students from outside Virginia who do pay the full freight.

A two-income family from New Jersey earning $120,000 a year, say, would pay tuition, fees, room and board of roughly $70,000 yearly for a child to attend UVA but would qualify for a mere $2,000 grant under the UVA Promise.

Increasing Price Resistance

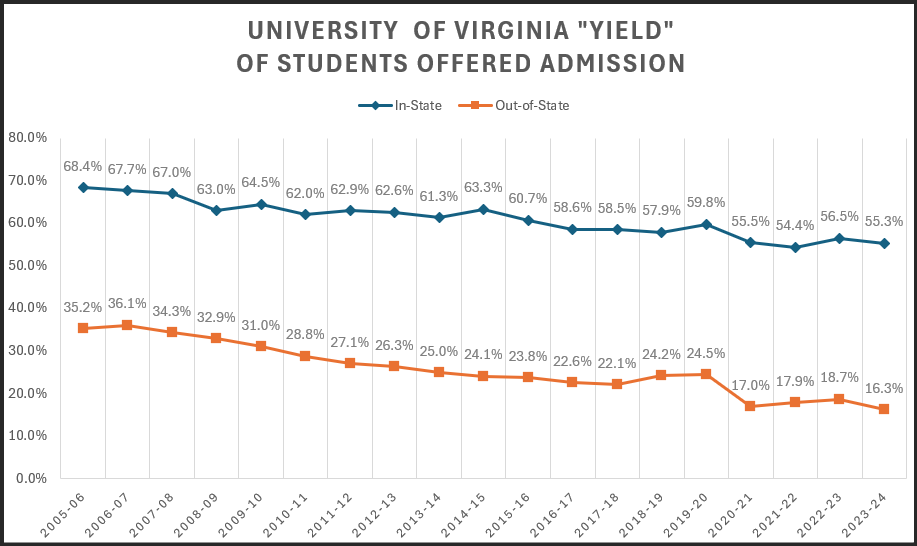

Increasing price resistance to the high cost of attendance can be inferred from admissions trends. UVA sets yearly records for the number of students applying to the University and plumbs new lows in the percentage of students accepted – commonly seen as a metric of exclusiveness and prestige. Those are the numbers the administration emphasizes in its news releases. But the percentage of students offered a spot at UVA who accept and enroll (referred to as “yield”) has been declining steadily over the past twenty years.

B08: Admissions Report FOR Four-Year Institutions (SOURCE: schev.edu)

Students applying to multiple institutions typically wait until all admissions offers have come in before making a selection. For many, the net cost of attendance — after accounting for financial aid — is a crucial factor.

As seen in the graph above, in-state students have been accepting UVA’s offer at a steadily declining rate. Yield has fallen from 68.4 percent in 2005-06 to 55.3 percent in 2023-24, down 13.1 percentage points.

The falloff is even sharper for out-of-state students. Yield has declined from 35.2 percent in 2005-06 to 16.3 percent in 2023-24, down 18.8 percentage points.

In-state students are less price resistant because state subsidies amounting to $13,600 — though low by the standards of other states — still make UVA an attractive option compared to peer institutions outside the state where they do not get the benefit of in-state tuition.

Out-of-state students do not enjoy state subsidies, so UVA’s cost of attendance seems exceptionally high by comparison to peer institutions, and the price resistance is commensurately stronger.

Conclusion

UVA’s business model requires a massive allocation of tuition dollars to financial aid. The diversion of tuition revenue to financial aid contributes to UVA’s escalating cost structure, which in turn requires higher tuition and fees to support. The financial edifice is unsustainable. Data suggest that UVA is facing increasing price resistance, especially among out-of-state students.

The encouraging news is that the Board of Visitors has the opportunity to turn the vicious cycle into a virtuous cycle by ordering cost cuts. Tuition and fees generated $691 million in revenue in 2022-23. Cutting administrative overhead by $100 million, to pick an arbitrary number, would allow the University to slash tuition and fees by a like amount. This in turn would reduce the need for financial aid by an extra $22 million, which could be applied to further tuition cuts. As a major bonus, by containing the cost of attendance, UVA would become more competitive in signing up the best and brightest students — both in-state and out-of-state.